|

WØUS Lyle B. Quinn Fairbury, NE Chapter # 25 QCWA # 3746 OOTC # 3286 |

|

|

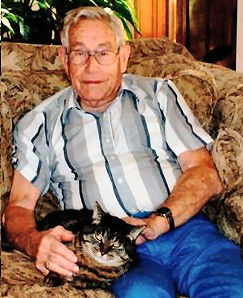

Lyle Brouse Quinn was born on November 26, 1918 in Fairbury, Nebraska as the first-born child of Leo Fredrick Quinn and Jessie Brouse Quinn. The grandson of Jefferson County pioneers; he spent most of his life in Fairbury. His early education was in the Fairbury Public School system. He continued his education at Doane College in Crete, Nebraska and graduated in 1941 with a degree in Physics. He was working in the Message Center in Washington, D.C. when Pearl Harbor was attacked late that same year. He spent the rest of World War II in the Army, serving as a radar technician on a Liberty Ship in the Pacific Theater. His unit waded into Japan after the surrender of that country. Lyle married Irene Kostlan Niedfelt in 1957. She preceded him in death in 2007. He is survived by their four children; Dr. James Quinn and wife Susan of Nebraska City, Nebraska; Mary Beadle of Columbia, Missouri; Mike Quinn and wife Julie of Fairbury; John Quinn and wife Darcy of Havana, Florida; five grandchildren and seven great-grandchildren; sister Mary Frances Quinn Kenney of Columbia, Missouri. He leaves numerous extended family as well as a host of friends and long-time associates. In addition to his family, a major life interest for Lyle was Amateur Radio work. He earned his radio license as a teenager and continued to be active in that work until recent years. His call letters, WØUS, indicate by the zero, that lowest number of any operator in the United States. This lifelong interest and public service was always a matter of quiet pride for him. Before the advent of the Internet, 'Ham' radio operators were essential to communication during emergencies and disasters. (They still are! N0UF, Bob, Webmaster) Lyle was an appreciated businessman and booster for his hometown, state, and country. He was an avid follower of Nebraska Cornhusker sports, both men and women. He will be fondly remembered and greatly missed. Services will be Saturday, April 16, 2016 at 11:00 a.m. at the First Baptist Church in Fairbury with Darlene Novotny officiating. Memorials will go to the Family.s Choice. Gerdes-Meyer Funeral Home in Fairbury is in charge of arrangements.

In Memory Of Lyle B. Quinn

November 26, 1918 - March 14, 2016 (Age 97)

Location: Fairbury, Nebraska

Lyle was born on November 26, 1918 and passed away on Monday, March 14, 2016. Lyle was a resident of Fairbury, Nebraska at the time of his passing. His early education was in the Fairbury Public School system. He continued his education at Doane College in Crete Nebraska and graduated in 1941 with a degree in Physics. Services will be Saturday April 16 2016 at 11:00 a.m. at the First Baptist Church in Fairbury with Darlene Novotny officiating. Memorials will go to the Familyas Choice. Gerdes-Meyer Funeral Home in Fairbury is in charge of arrangements.

Lyle Quinn, WØUS, celebrated his 90th birthday on November 26, 2008.

The Army called on civilians to assist in communications. Lyle returned the call and made his way to Washington D.C. Lyle Quinn of Fairbury Nebraska, has a love for his ham radio that dates from 1935, over 70 years. Those the army employed were not considered Army personnel but Civil Service Employees. I had just graduated from Doane College and it sounded pretty good to me, he said. "Because I knew sooner or later I'd have to get involved, you know, the draft was starting." About one month later Lyle was in Washington D.C. working in the Munitions Building.

When construction of the Pentagon was completed, his department moved there. The Munitions Building was demolished in 1970. On the afternoon of Dec. 7, 1941, Quinn and a friend were listening to a football game on the radio. Later that evening they received word that Japan had bombed Pearl Harbor in Hawaii. The two decided they would walk to the White House and watch the "notables" come and go. "We got in on the excitement a little bit," Quinn said. It was now time for Quinn to put his coding and copying skills to the test. The Munitions Building served as a clearing-house for all messages handled within the military system of communications. The US was divided into core areas with a headquarters in each area. Each area had their-own message handling system. If one core area wanted to send a message to another core area, the message would have to be sent through Washington D.C. before being sent on.

"That's what we handled," Quinn said. "There were anywhere from 7 to 13,000 messages a day being handled by hand." Not only did the Munitions Building have direct contact with the core areas, but also Honolulu, HI and San Juan, PR. "There was a lot of secret stuff handled in five letter code groups. We would copy the whole message with no idea what it was about. We just knew where they came from and where they were going." The messages went to another room to be decoded. "I had to laugh one time. I was walking home with a guy one morning after we worked all night and he said he was sick and tired of decoding messages all night and getting out and reading them in the morning paper," Quinn chuckled.

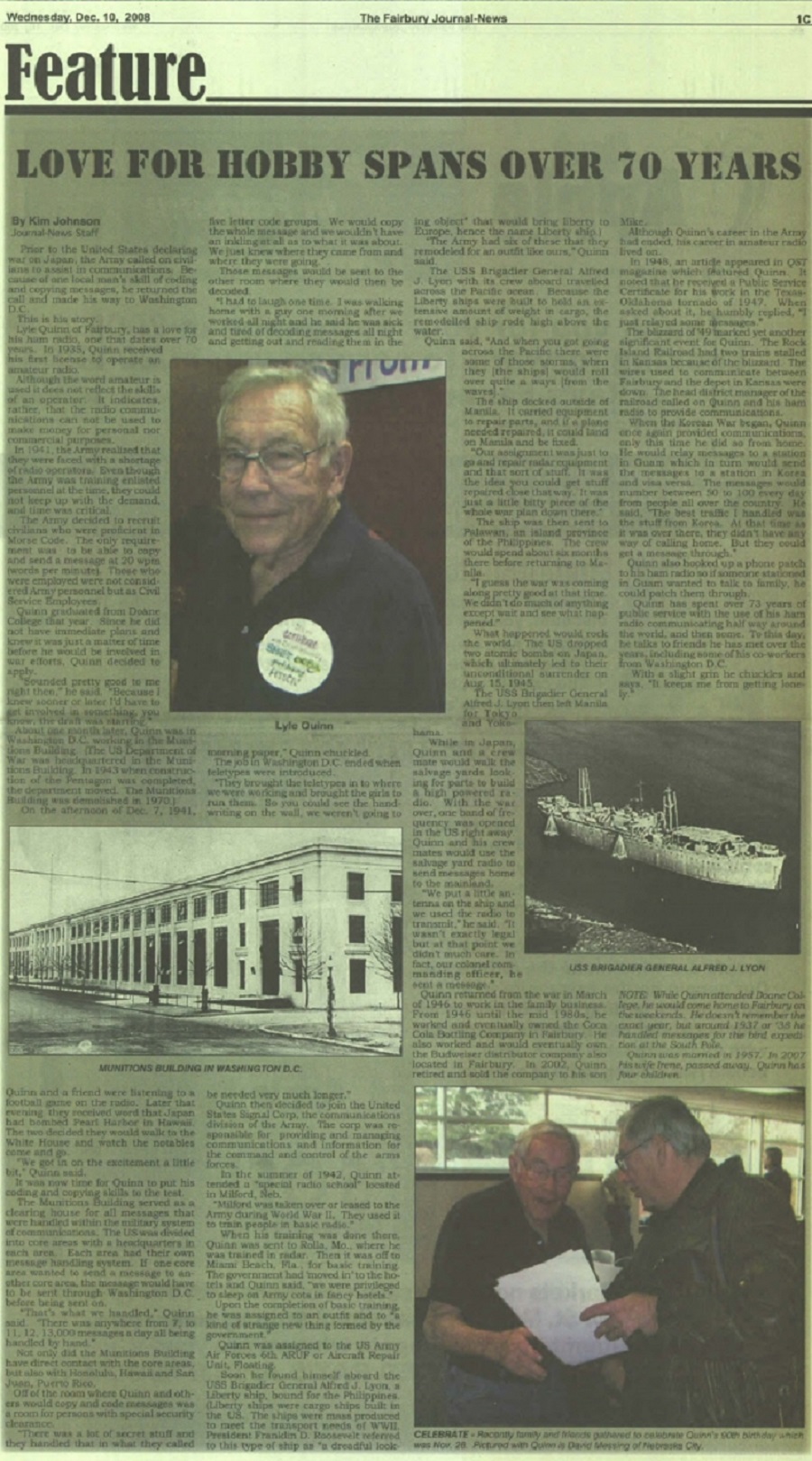

The job in Washington D.C. ended when teletypes were introduced. "They brought in the teletypes and the girls to run them. The handwriting was on the wall, we weren't going to be needed very much longer." Quinn decided to join the United States Signal Corps, the communications division of the Army. The Corps was responsible for providing and managing communications and information for the command and control of the armed forces. In the summer of 1942, Quinn attended a "special radio school" in Milford, Neb. "Milford was taken over or leased to the Army during World War II. They trained people in basic radio." When his training was finished there, Quinn went to Rolla, Mo., for Radar training. Then it was off to Miami Beach, Fla., for basic training. The government had 'moved in' to the hotels and Quinn said, "We were privileged to sleep on Army cots in fancy hotels." Basic training complete, he was assigned to "a kind of strange new thing" the US Army Air Forces 6th ARUF or Aircraft Repair Unit, Floating. Soon he was aboard the USS Brigadier General Alfred J. Lyon, a Liberty ship, bound for the Philippines.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt referred to this type of ship as "a dreadful looking object" that would bring liberty to Europe, hence the name Liberty ship. "The Army had six that were remodeled for an outfit like ours," Quinn said.

The USS Brigadier General Alfred J. Lyon with its crew aboard crossed the Pacific ocean. The Liberty ships were built to hold a large amount of weight, the remodeled ship rode high above the water. "And going across the Pacific some of the storms rolled the ship over quite a way." Quinn said. The ship docked outside of Manila. If a plane needed repair, it could land on Manila to be fixed. "Our assignment was to repair radar equipment and that sort of stuff. The idea was to get repairs close that way. It was a little piece of the whole war plan." The ship was then sent to Palawan, an island province of the Philippines. The crew would spend about six months there before returning to Manila. What happened next rocked the world. The US dropped two atomic bombs on Japan, which led to their unconditional surrender on Aug. 15, 1945. The USS Brigadier General Alfred J. Lyon then left Manila for Tokyo and Yokohama. While in Japan, Quinn and a crewmate would walk the salvage yards looking for parts to build a high power radio.

With the war over, one band of frequency was opened in the US. Quinn and his mates would use the salvaged radio to send messages to the mainland. "We put a little antenna on the ship." he said. "It wasn't exactly legal but at that point we didn't much care. In fact, our commanding officer sent a message."

Quinn returned home March 1946 to work in the family business. By mid 1980s, owned the Fairbury Coca Cola Bottling Company and eventually owned the Fairbury Budweiser distributor Co. Quinn retired, sold the company to his son Mike. Amateur radio lived on. A 1948 QST article shows Quinn receiving a Public Service Award for work during the 1947 Texas-Oklahoma tornado. The blizzard of '49 marked yet another significant event for Quinn. The Rock Island Railroad had two trains stalled in Kansas because of the blizzard. The district manager called on Quinn to provide communications.

When the Korean War began, Quinn again provided communications, this time from home. He would relay messages to a station in Guam, which in turn would send the messages to a station in Korea and visa versa. The messages numbered between 50 to 100 every day for people all over the country. Quinn also hooked up a phone patch so those stationed in Guam could talk to family.

NOTE: While Quinn attended Doane College, he would come home to Fairbury on the weekends. He doesn't remember the exact year, but around 1937 or '38 he handled messages for the Bird expedition at the South Pole. Quinn was married in 1957. In 2007 his wife Irene, passed away. Quinn has four children.

Fairbury Journal/News; Wed, Dec 10, 2008 front page Article

Article