|

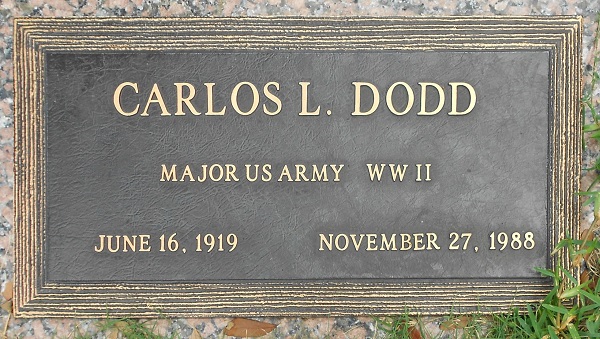

Carlos L. Dodd New Boston, TX Moorestown, NJ Sterling, VA Dallas, TX QCWA # 5410 |

|

Texarkana News - by James Presley-Special to the Gazette Jun 24, 2018 @ 2:54am

THE PILOTS OF RED SPRINGS: How four Bowie County farm boys took to the air in World War II

When they were boys before World War II, all four lived within two miles of each other, a distance traversed easily and regularly on foot in those days.

Carlos Dodd is pictured in his Air Corps uniform. About 1943, he transferred from the Air Corps to the Coast Artillery. He was selected to study radar at MIT while radar was a deep secret. (submitted photo)

Acknowledgments for Carlos Dodd photos and information: Hazel Dodd Rehak, Glenn Dodd, Betty Ayers Dodd, Retta Rutherford, John R. Dodd and Carol Dodd Lemons

In the war, they distinguished their little farming community in a way few, if any, other rural entities its size could boast: all four trained to be pilots in the class that became known as the Greatest Generation.

Youths everywhere flocked to the colors in droves, but four pilots from such a small place? It may well have been unique.

Red Springs, eight miles west of Texarkana, was so sparsely populated that in the hotly contested July 1942 election, only 41 residents voted.

By then, the portion north of US Highway 67 had been sheared off to build the defense plants, (Red River Army Depot and Lone Star Army Ammunition Plant). Ballots were cast at the seventh-grade Red Springs elementary school until the 1939 consolidation with Redwater Independent School District and after that at the Red Springs Baptist Church, on the old two-lane US Highway 67 (now Farm to Market Road 991). The box was still labeled Trexler after its original location on the Cotton Belt railroad several miles to the south. It was one of the smallest voting boxes in Bowie County. It had two small stores, a Baptist church and the school until 1939, but not even a post office.

The country was still reeling from the Great Depression when shadows of war first appeared, reshaping everyone's life.

Heading for pilot training were:

o Carlos Lester Dodd, born 1919.

o John Wesley Head, born 1920.

o Virgil Woodrow Head, John's brother, born 1923.

o Lloyd Leslie West, born 1922.

Despite their being so much older, I knew them all, although I met Carlos Dodd only once and briefly. The other three I came to know well and over time. The Head brothers were neighbors. Lloyd West was my second cousin.

They are all dead now. Virgil Woodrow Head was the last to die, in 2006. When I interviewed him, he was the only one of them still living. Surviving relatives, documents and photographs provided material about him as well as the other three.

Growing up in the 1920s and 1930s, they came of age when airplanes were still new and their pilots glamorous. The sight and sound of an airplane drew entire families out of the house or halted work in the field to witness it. Charles A. Lindbergh's dramatic 1927 flight across the Atlantic to Paris still inspired wonder. The ill-fated 1935 crash of Wiley Post and Will Rogers in Alaska remained a fresh memory. The pilot's life was rare and exotic. For millions over the world, flying was the next frontier.

Their condensed biographies track their contributions to the war effort and how they spent the rest of their lives.

Carlos Lester Dodd was born in the Dalby Springs community in western Bowie County on June 16, 1919. He was the oldest of the four and the only one with a college degree when the war began.

His sister Hazel Dodd Rehak recalled he was born at Dalby Springs, but one record stated it was New Boston, suggesting he cited the larger entity that would be better recognized. He attended Texas A&M University at College Station, went through ROTC training there and graduated in June 1941 with a degree in Industrial Engineering and a second lieutenant's commission in the Army. He immediately began active duty just months before the Pearl Harbor attack on December 7.

"He was a Renaissance man in many respects," his son John Dodd said, and the evidence bears that out. He led a fascinating life that included postwar pioneer engineering in television and other fields.

Dodd's interest in flight began long before he left for college. He gained his education during the Depression, finishing Red Springs' seven grades and graduating from Redwater High School. A serious student, he also excelled in sports, especially basketball.

Life on the small family farm in the 1920s and 1930s was hard. He helped his father chop wood for the family and for sale. They raised and sold vegetables in Texarkana. His mother kept about 500 chickens and sold eggs. He was five years older than his sister Hazel, 10 years older than brother Glenn.

As a boy, Carlos became interested in radio, foreshadowing his postwar career in communications. At age 16, he made his own crystal set when few owned a radio. Neighbors came from time to time to listen to broadcasts.

Another major interest was aviation.

Like other boys his age (Lloyd West was one), "he built model airplanes and dreamed of flying," as his first wife Betty, who wrote a brief biography of him, put it. He also dreamed of getting an education and leaving the farm for the wider world and its opportunities. He saw Texas A&M at College Station as his vehicle to achieve that dream.

Like many other youths during the Great Depression, he worked his way through college. He hitchhiked, without money, to College Station to enter A&M. A professor found him a place to sleep in the basement of a building on campus. At one point his father gave him a calf, which he later sold to defray expenses. He worked odd jobs, mowing yards, washing dishes, waiting tables in the college dining hall, whatever he could find to do. In addition to on-campus military training, he attended summer drills.

Then, in his sophomore year, his father, Clyde Dodd, sustained a fractured back in an automobile accident. Clyde couldn't work. Carlos had to return to Red Springs to help run the farm. That could have been the end of his dream, but while operating the farm he also enrolled at Texarkana College. This meant he didn't lose the entire year's education. His father's back healed so that he could resume work, and Carlos returned to A&M.

Carlos' brother, Glenn Dodd, who later made the Air Force his career, remembered his older brother as "pretty quiet, a serious type. He didn't joke at all." As a senior at A&M, Carlos put up $65 to the ROTC program in order to take flight lessons at the Bryan, Texas, airport, on the condition that he would go into the Army Air Corps following graduation. He did, with enthusiasm.

During his college days, according to his son John, he played football when All-American fullback Jarrin' John Kimbrough starred for A&M. Another fascinating anecdote from those days is that Carlos' roommate was George Gay Jr. from Waco. During the war, Gay was to become the only surviving pilot of his 15-plane torpedo squadron on the U.S. carrier Hornet in attacks on Japanese ships in the Battle of Midway in June 1942, a major victory that helped turn the tide at a critical time. Gay, his plane shot down, floated in the ocean and watched the battle close-up until he finally was rescued, a scene dramatized in the movie Midway.

Sensing that war was imminent in mid-1941, Dodd, like many others seeking overseas assignments, volunteered for The Philippines. However, the quotas filled before he had a chance. He was fortunate. If he had gone, he might well have been in the infamous Bataan death march that ended in Japanese POW camps for those who survived.

He proceeded to train as a pilot in a series of bases in Arizona and West Texas.

Despite his flying skills and dedication, he transferred out of the Air Corps before getting his wings. The reasons were two-fold. His second wife Retta explained that one of his subsequent instructors told him to land at a lower RPM than Carlos concluded was safe. "Carlos knew it would have caused a crash," she said. An engineer with a precise mind who understood his plane's capabilities, he disputed the instruction and considered alternatives.

Secondly, after logging enough hours in training to qualify for a private pilot's license, he was recruited for what then was a secret electronics training program, and he seized the opportunity.

He became a radar officer.

When a cadet does not complete his pilot training, he reverts to his previous rank. In Dodd's case he lost no status, because he had entered as a second lieutenant and remained an officer.

It was around 1943, his sister Hazel said, that he transferred from the Air Corps to the Coast Artillery, selected to study radar "while radar was a deep secret. He did this study at MIT."

He could not even tell his family what he was doing. The highly secret new technology could be used to guard the coast. The United States was at risk from German submarines on the Atlantic side and Japanese subs from the Pacific. He was dispatched for training to Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Boston. Upon completion of the training, he was promoted and stationed in the Coast Artillery at Camp Edwards on Cape Cod, Mass. He was there seven months and married Betty Ayers at Cape Cod. He also taught servicemen at MIT and Harvard during that time.

His sister Hazel, then a student at Texas State College for Women, now Texas Woman's University, made the trip to Cape Cod during that time.

Subsequently, Dodd became a radar instructor for a year at Camp Davis at Wrightsville Beach, N.C. He then went to Fort Bliss, Texas, for reassignment. Because the Allies had gained air supremacy over the German Luftwaffe sooner than expected, the Army shifted Dodd's expertise to the Field Artillery. In Orlando, Fla., he trained to use radar against enemy forces in the Pacific theater.

Unexpectedly on the European front, the Battle of the Bulge began in mid-December 1944 and continued for a month. To meet the emergency, the Army transferred Dodd's outfit to the Infantry. With the German army thrown back in January 1945, and the war moving toward its final months in Europe, Dodd returned to Fort Bliss where he joined a pool of radar officers for reassignment. In March 1945, he arrived at Fort Sill, Okla., for intensive training on guiding mortars in the projected invasion of Japan.

The atomic bombs at Hiroshima and Nagasaki ended the need for the invasion.

Maj. Dodd, on terminal leave pending discharge in March 1946, returned to the family farm in Red Springs in December 1945.

Carlos maintained his interest in flying, long after the war.

Subsequently, he held a private pilot's license and at times rented planes at the Texarkana Airport and took family members up, including his father Clyde, sister Hazel and brother Glenn. Hazel remembered the small planes on which Carlos would take family members around the Ark-La-Tex. Years later, he owned his own plane.

His postwar civilian career was devoted to pursuing the booming electronics industry that brought television into every American's life.

Building on his Army experience in radar, he studied television technology at RCA Institute in New York City for two years.

He next headed to Fort Worth as a television engineer at WBAP, which he helped enter the TV world in 1948. He was part of a team that first televised a football game locally in the Cotton Bowl for WBAP-TV that fall, the Red River Rivalry between Texas and Oklahoma. He did some of the camera work. Next as chief engineer for WDSU in New Orleans, he led a team that initiated television there. WFAA in Dallas hired him as chief engineer in 1950 for the same mission.

During the next decade, by which time he and Betty had three childrenCarol, John and Jameshe shifted his career into sales. Electronics was sky-rocketing. He traveled frequently and virtually worldwide. He worked for Motorola, then Collins Radio, which dispatched him to Mexico City in 1962 to open an office. Ever energetic and always the student, he also enrolled in business administration at the Universidad Nacional de Mexico while there.

He then moved to Washington, D.C., with Page Engineering, which built electronic systems around the globe. In New Jersey, he became involved in research and development of electronic games and key cards for hotels. At one point, he started his own company but failed to secure sufficient funding. Then he traveled to sell a device for troubleshooting computers.

In 1980, he came full circle when a firm transferred him to Dallas with a product using electronics in oil drilling. His second wife Retta described the measurement-while-drilling device as "a computer on the end of a drill bit, sending data to the surface." When the oil patch took a hit in the 1980s, the concept suffered but eventually became widely used.

By 1982, he and Betty had separated and divorced. A few years later he met Retta Walker at a tennis club in Dallas, where they were randomly paired and learned they had common interests. When he later proposed, he explained he'd been diagnosed with prostate cancer years before and pointed out the two-decade difference in age. She accepted. By then China was the only major country's capital he hadn't visited, so they went, via Manila and Tokyo, to Beijing, Hangzhou and Shanghai. But their happy marriage was to be short-lived.

On Nov. 27, 1988, he died unexpectedly, not of cancer but of a cerebral hemorrhage. The farm boy who had made himself a pilot, an electronics pioneer and a world traveler had packed a couple of lifetimes into his 69 years.